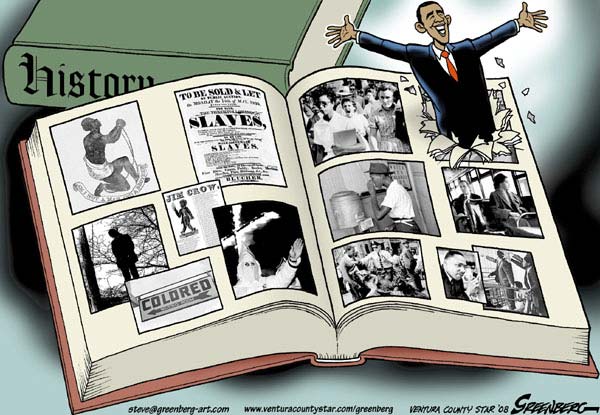

The most insightful essays on photojournalism typically have included keen attention to the social and political implications of the photographic technology itself. The ideas and attitudes that become influential often persist despite technological change–sometimes rightly so, but not always. One item of conventional wisdom that needs to be either updated or shelved is the anxiety about media spectacles.

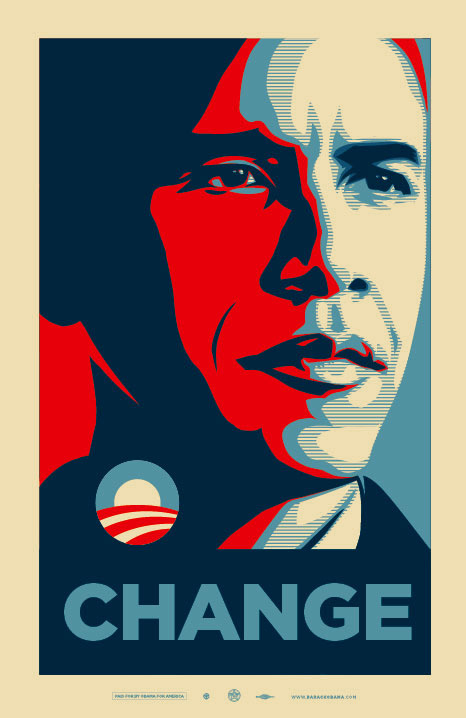

This image is a lovely vignette of the digital age. The caption stated that the woman in the center was showing “passers-by a photograph that she had taken of President-elect Barack Obama’s motorcade.”

We don’t see what they are seeing, but we do see how they are seeing it. Clustered together on a busy city street, focused as one on the small screen, blending their distinctive reactions, these strangers have become civic friends for a moment though an act of shared spectatorship. The remain individuals with distinctive modes of response–curiosity, pride, studiousness, and wonder, and with that four variations of a good feeling–but they obviously have been pulled together, however briefly, as if they they had other things in common as well. Though still strangers, they are also citizens defined by their comfort with each other while looking together at one sign of political representation.

It is significant that we see only her camera, not the picture taken. The content of the image does not matter as much as the fact that she can take it and share it. This everyday event thus reflects major social realities: it is understood that no guard is going to come along and confiscate the camera, that people can interact casually on the street as equals, and that the photograph typically is taken to be shared. It also is evident how digital technologies are inflecting the conventions for taking and interacting with images: cameras are everywhere and no longer tied to special occasions such as travel, the photograph is immediately available for review and other use, any place is a suitable place to view the image, and it could end up just about anywhere. The passers-by can look over her shoulder because they all have already done something like that many times before. Indeed, one consequence of affordable cameras and especially of the ubiquity of digital cameras may be that they prompt and normalize interactions among strangers. Whether asking someone to take your picture to holding up the camera phone image for all to see, one is crafting a public in miniature.

It also may be significant that the image is so small. Although the viewers’ reactions suggest an aura of political authority, the camera is also cutting it down to size. Likewise, the phantasm of Big Brother on the giant screen dominating all consciousness is seriously out of place here. There still are big screens, of course, and billions of dollars poured into major media productions, but digital technologies also are radically democratizing visual culture. In place of the mass media spectacle, there are small moments of shared seeing. To understand that well, we need to get beyond high anxiety about the media spectacle. Less attitude and smaller concepts doesn’t sound like a prescription for academic stardom, but it might be just what is needed to understand visual democracy.

Photograph by Ozier Muhammad/New York Times.