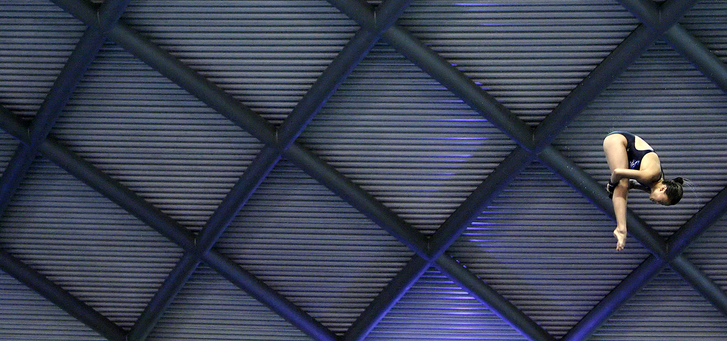

We almost never write about sport at this blog, yet I’m putting two posts up this week on the run-up to the Olympics. Maybe it’s because the war in Iraq is all but won–based on recent coverage, anyway–so I need something new to talk about. More likely the increase in coverage is producing a fresh crop of images. Here’s another one that caught my eye:

The New York Times story featured China’s heavy investment in rowing as part of its push to win the medals competition. The enormous investment is very real, but the whole idea seems quaint–just the thing you’d expect from a somewhat socially backward newcomer. Does anyone really care if medal total goes to China, the US, or the USSR–whoops! I mean Russia? The whole game is a relic of the Cold War. Aren’t such symbolic measures meaningless next to the real competition for oil, markets, and global economic dominance?

The short answer is yes, and the photo above illustrates just how the game is changing. Two things immediately define the image: the athlete’s magnificent physique and the high-end modernist decor. He is a superbly trained athlete walking through the functionally designed training facility. Both have all the marks of smart and lavish investment. Any difference between his individual person and the impersonal setting is covered over by their uniform simplicity and shared engineering.

The signage on his shirt and the wall also are part of the image. CHINA marks him as member of the national team, but this is not the flag-waving patriotism of a public ceremony. That shirt could just as well say NIKE or any other logo–you are looking at the new international style, another iteration of the high modernist culture of scientific training, standardized competition, and expert performance that links the top-tier athletes across the globe. By contrast, the Olympic rings and number on the wall look like crafts project from the local school–clearly a temporary addition. Cute, but hardly essential. After all, the Olympics are only the next event in an unending push for optimization.

In short, we can see the nation-state becoming a platform for economic and organizational power. This arrangement has enormous productive capacity and clearly can benefit some individuals. As it happens, however, much of what used to distinguish both the nation and interaction across national borders is changing, perhaps withering away. The contrast is even more evident when looking at another photo:

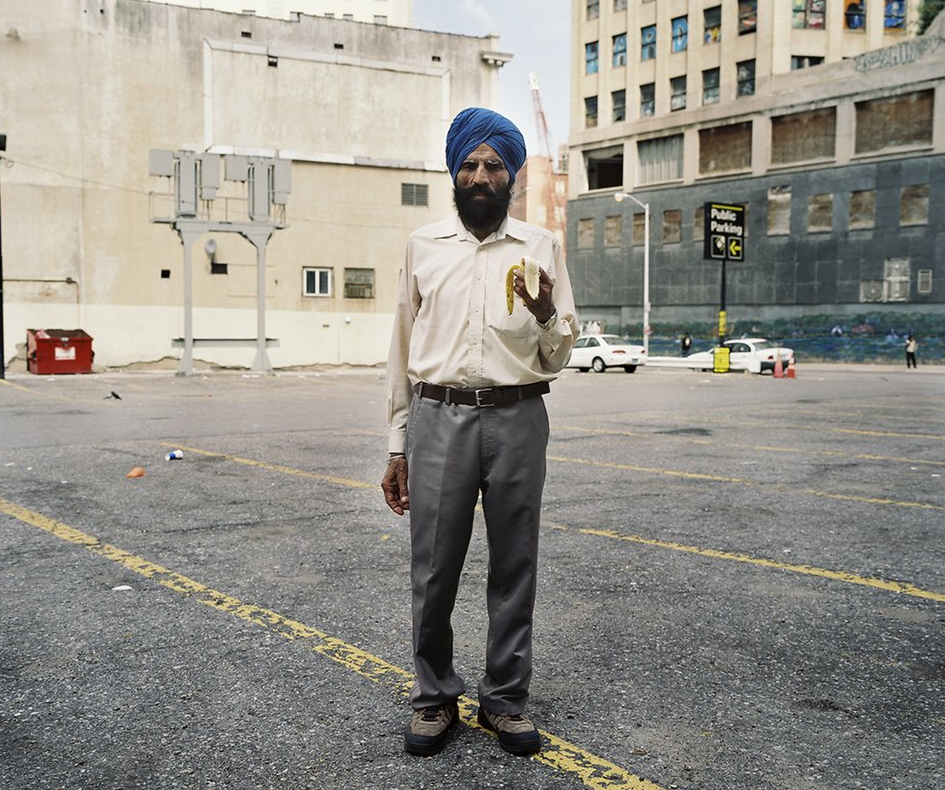

A boxer is being wrapped in a Brazilian flag prior to a qualifying bout for the Olympics. Boxing, which had a good run in the twentieth century as one of the premier sports nationally and internationally, is all but extinct. The setting in this photo does not suggest strong financial support. The flag is the only lavish thing there–colorful, rich material with plenty of drape to cover his body. Needless to say, it will come off very soon. The image is touching, really: this poor kid about to get beat on is putting on the national flag to become something larger than himself. It will be done to get the crowd on his side and intimidate his opponent, but not only for that. He wants to look good in that flag, and he’s proud to wear it. And that flag probably is about the extent of the support he will get from the state. Brazil has a lot going for it, but it’s still content to be a collective, not a platform.

That boxer probably could do a lot with Chinese training. But don’t feel sorry for him, for there is one more thing to see. It’s a coincidental effect in each case, but nonetheless food for thought. Standing amidst not much of nothing, the boxer is looking up, head held high. His face already looks cut, but he is unbowed. Now look again at the Chinese athlete. He is strong, perhaps thoughtful–going over the training routine one more time–but his head is down, as if habitually, submissively so. As if accustomed to the yoke. He is beautiful, but he is not free. Whether due to the state or the discipline, he is not free.

Photographs by Doug Kanter/New York Times and Rodrigo Abd/Associated Press.

0 Comments